Jason McDonald and Timmy Gipson were responsible for this fascinating 2-day workshop on green tea processing. I take the liberty of saying ”fascinating” even though I wasn’t physically there because it fascinated me from the start of the concept to the finish when I “attended” via iPhone.

The idea behind this workshop was to show how each kill-green process works and what each process brings to the cup. Kill-green is the phrase the Chinese use to describe the processes whereby the enzymes in the leaf are denatured and no longer play a role in the tea’s flavor development.

|

The Great Mississippi Tea Company's new garden in the mist. It will be ready for harvest in a few years.

As part of the workshop, Jason explained in detail how they go about preparing the soil and growing their plants to yield their exquisite teas. |

|

| Sorting the leaves. |

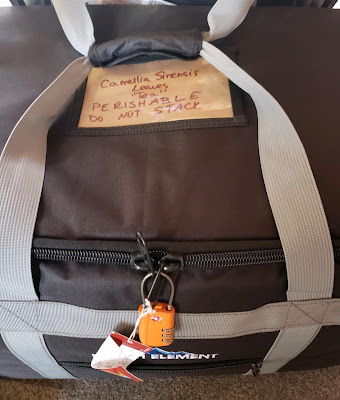

To keep the leaves from jumping the gun and producing and then losing too many delicious stress chemicals before processing in Vegas, the leaves were transported in darkness with ice packs and moisture in a big rucksack.

Most of the leaves made it safely to Vegas, though some were too close to the icepacks and suffered a bit.

Once in Vegas, the leaves were allowed to wither overnight, then Jason and Timmy brought them to the Convention Center, ready to undergo the kill-green processes.

|

| The leaves in Vegas, ready to be processed. The wok and boiling pot are on the table, along with a big sieve to capture them. |

After the kill-green discussed below, it was time for the leaves to be rolled in muslin, then dried. Here you can see the muslin cloths after rolling. The difference on color is quite striking. Normally you would expect the muslins from steaming (on the right) to be very pale, but as you can see they are brown, suggesting over-cooking.

|

| Muslins after rolling. |

It is important to note that for each pair of the kill-green processes, one group of people carried out one timing, while another group carried out the other timing. The differences in the flavors of the pairs may therefore not only be the result of timing, but also result of subtle differences in handling of the leaves.

When it came time to taste the brewed teas, I was invited in by iPhone to share in people’s comments and to ask and answer questions. I took notes and Jason sent me his. The following results are compiled from these two sources.

|

| Witnessing the tasting by iPhone! |

What were the results?

|

Leaves and liquors from the four processes. Clockwise from top:

Pan-fired: left 5 minutes, right 10 minutes;

Steamed: left 2 minutes, right 45 seconds;

Sous-vide: left 20 minutes, right 10 minutes;

Boiling: left 1 minutes, right 2 minutes.

The photo does not accurately reproduce the colors of the leaves. See below. |

1) Pan-firing in Chinese and Korean manner:

For this process the leaves were tossed in a wok. The advantage of this method is that the tea gains a slightly nutty toasty quality. The disadvantage is that the leaves can burn if you don’t keep tossing them and turning them over completely.

|

| Tossing leaves in a wok. |

One of the most curious results of the pan-fired processing was that the 5 minute firing had more of the toasty quality than did the 10 minute firing, which was judged to be more vegetal and greener, even buttery, though still toasty. The 5 minute was bitter while the 10 minute was sweet.

As you may be able to see from the picture, the 5 minute was somewhat darker as well, suggesting more oxidation and also more Maillard browning products, which give the toasty quality.

One possible explanation for the unexpected findings may lie in the handling. The 5 minute leaves may simply have gotten too hot.

2) Steaming in the Japanese way:

|

| Steamed leaves: left 1 minute, right 45 seconds. |

Steaming also yielded a paradoxical result, possibly explained by issues with the steamer. It has been suggested that the Las Vegas altitude and lack of humidity might account for the results. However, water turns into vapor at a lower temperature at higher altitude and lower humidity, so the observed burnt quality at 45 seconds would have been less rather than more likely.

The 45-second steaming gave a darker leaf, with uneven color, as if some of the leaves had been properly steamed and some had become too hot. This problem was confirmed at the tasting, where the 45-second tea was found to be less grassy than expected, and to have black tea notes. At the same time, the 45-second steam also didn’t allow enough time for breakdown of the leaf’s cell walls, so it was harder than the 2-minute to roll.

The 2-minute steaming gave a more classical green tea: lighter, more grassy, more vegetal, bitter and astringent.

3) Blanching in boiling water, as home-growers of tea might do:

|

| Blanched leaves: left 1 minute; right: 2 minutes. |

At 1 minute the tea seemed more like what you would expect a green tea to be. The hairs on the tips remained, the roll was lighter so the cell walls were adequately broken down. The flavor was green and vegetal, somewhat bitter while buttery and light, with slight roastiness suggestive of pan-firing.

Two minutes was perhaps too long for blanching: there was an abundance of yellow stems from overcooking. On the other hand the brewed tea was lightly vegetal and smooth according to some. According to others the brewed tea was bitter with a biting astringency! Another variable one has to take into account in processing is the difference in taste sensitivity among people, especially when it comes to bitterness and astringency.

4) Sous-vide:

|

| Sous-vide: left 10 minutes; right 20 minutes. |

Sous-vide was the most successful method of the four, as both 10 minute and 20 minute processing yielded pleasant teas. I believe that this method is successful under “amateur” circumstances because it involves the fewest variables. The temperature of the bath is constant, there are fewer chances of one clump of leaves becoming more heated than another, and the vacuum means that oxygenation is stopped the moment all the air is sucked out of the bag.

The 10-minute tea was fluffy, with white tips still in evidence. The “green” aroma chemicals were less developed than were those in the 20-minute tea. The 20 minute tea was more vegetal, with a well-rounded though still bitter and grassy taste, and a dry, slightly buttery after-taste that induced salivation.

Conclusion

Perhaps the most obvious conclusion from this workshop is that processing leaves for tea is not easy. There are so many variables that come into play, over many of which we have limited control. What would seem to be simple is in fact extraordinarily complicated—as complicated as the chemical processes in the leaf, and as sensitive to growth conditions and handling.

IMPORTANT ===>>>

Want to learn more? Jason and Timmy are preparing to host an exclusive limited-attendance tea plucking and processing workshop at The Great Mississippi Tea Company farm this coming September!

Keep an eye on Facebook for specifics!